The implosion of a company with ties to South Africa’s wine country has caused a hangover for one of Wall Street’s most opaque businesses.

When shares in Steinhoff International Holdings NV cratered in December, global investment banks lost more than $1 billion tied to so-called corporate equity derivatives. That’s equivalent to almost one-third of the revenue generated last year from such deals, which allow large clients to use shares to fund investments.

The scale of the losses has shaken up a business that’s grown as stock markets surged and been a key source of funds for banks’ most prized customers: billionaires, sovereign wealth funds and acquisitive Chinese conglomerates. Some lenders are now pulling back, selling assets or questioning the size of future transactions as risk officials across the industry ask more questions, executives said. Others see opportunity and have moved on to arrange more complex trades for deal-hungry clients including Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co. founder Li Shufu.

“Some banks are stepping away, some banks are stepping into the breach,” said David Stowell, a finance professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, who previously helped run equities businesses at firms including JPMorgan Chase & Co. “It’s not as if there’s less competition in the wake of Steinhoff.”

The Steinhoff trade that soured was a margin loan, a popular corporate equity derivative that allows a client to borrow from banks using shares as collateral. Other types that have been used frequently are so-called collar trades, which allow investors to amass stakes while protecting themselves against a decline in stock prices.

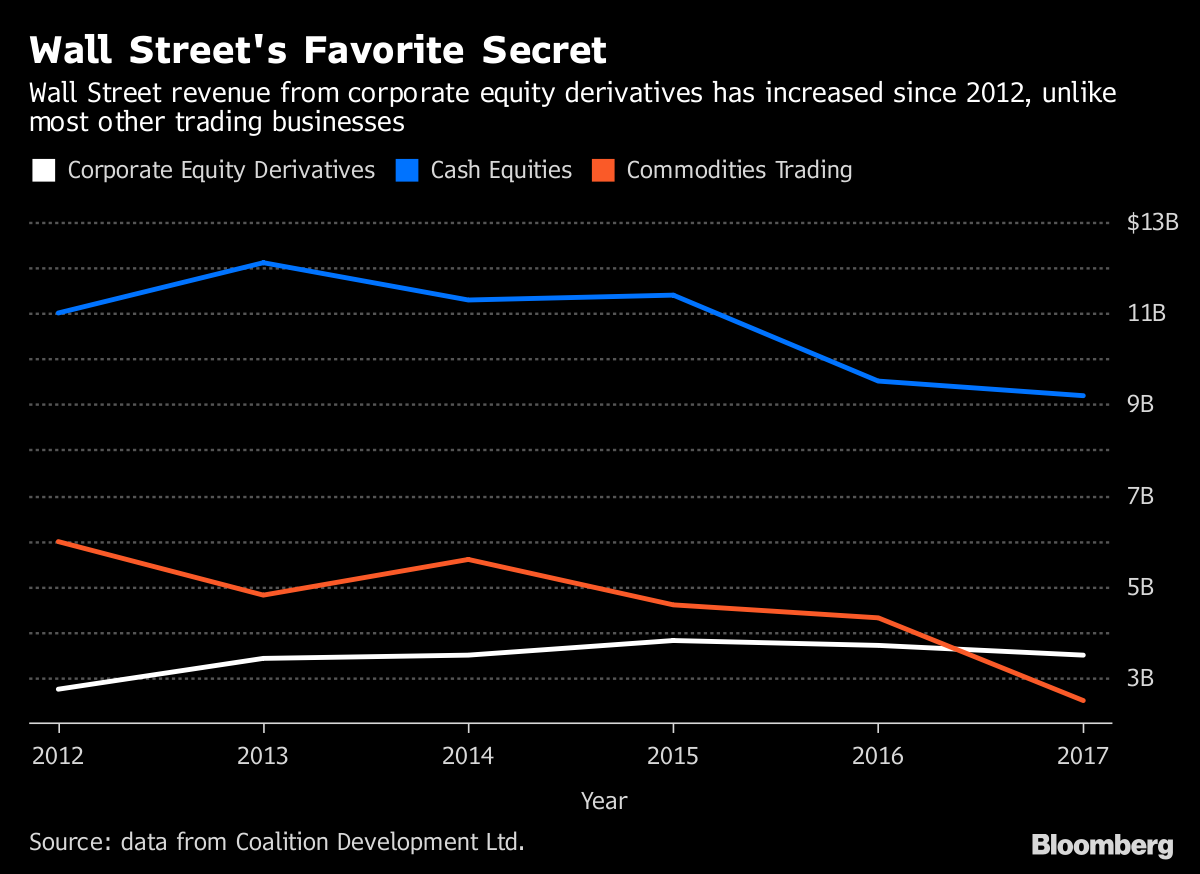

Wall Street's Favorite Secret

Wall Street revenue from corporate equity derivatives has increased since 2012, unlike most other trading businesses

Source: data from Coalition Development Ltd.

The business, which went through boom-and-bust cycles before, has grown as soaring stock markets prompted clients to do more trades and is now bigger than trading oil and gold. The 12 biggest banks generated about $3.5 billion in revenue from arranging the contracts in 2017, a 28 percent increase compared with five years ago, according to data from Coalition Development Ltd. Trading in plain stocks and bonds declined in that time.

Geely, a Hangzhou-based automotive company, bought a 7.3 billion-euro ($9.1 billion) stake in Daimler AG in February using the biggest collar trade of its kind, Bloomberg has reported. HNA Group Co. used margin loans and collar trades from lenders including UBS Group AG and JPMorgan as it spent more than $10 billion buying shares in Deutsche Bank AG and a group of Hilton property companies last year, filings show.

The business has been lucrative for Wall Street banks because the products are complex, tailored specifically for each client and aren’t traded on exchanges. Yet lenders have been taking risks for less money as competition increased.

‘Largest Loss’

Christo Wiese

Photographer: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg

In 2016, then-Steinhoff Chairman Christo Wiese borrowed about 1.25 billion euros ($1.5 billion) from a group of lenders, pledging stock in the company as collateral, filings show. The debt had an interest rate of about 125 basis points above the London interbank offered rate, people familiar with the matter said. That’s lower than the 1.87 percent average cost of borrowing for corporations around the time of Sept. 2016, European Central Bank data show.

The deal went bad when, over just two days in December, Steinhoff’s shares plunged 80 percent amid accounting irregularities, flummoxing teams of bankers in London and triggering what JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Financial Officer Marianne Lake called “far and away the largest loss in that business that we’ve seen since the crisis.”

Steinhoff, a global retailer with a local base amid the vineyards of South Africa’s Western Cape, is a reminder that “equity financing is not a riskless business,” said Stephane Manchet, head of equity solutions for Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc. in London.

‘Wrongway Risk’

Bankers and traders who arrange the deals are now facing more questions from colleagues in risk departments about their multibillion-dollar margin-loan portfolios, according to officials across U.S., European and Asian banks, who requested anonymity as the matter isn’t public.

Bank of America is among lenders looking to sell some of the debts and scale back its operations, and plans to change the structure of future deals to let it react faster to head off losses, Bloomberg has reported.

Banks are particularly spooked by margin loans that have “wrongway risk,” executives said. This is when a borrower’s financial health is too closely linked to that of the shares pledged as collateral and they both decline at the same time, as was the case with Steinhoff, they said.

“The products have good profitability, but they have difficult profit profiles,” said Daniel Fields, head of global markets at Societe Generale SA until 2016. “They generally make reasonable returns over time, but they will create occasional large losses and that is difficult to manage.”

Facing Questions

Citigroup Inc. and Nomura Holdings Inc. are reassessing the size of margin loans they want to do in the future, the people said. At JPMorgan, the biggest player in the industry, traders are trying to figure out how they can change the process of arranging transactions to prevent another debacle, one person said. Even at Morgan Stanley, which wasn’t involved in the Wiese deal, scrutiny of the debts has increased.

“A fiasco such as this receives a lot of internal attention,” said Ronald Colombo, a former counsel to Morgan Stanley and now a law professor at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York. “It can create a very tense, uncomfortable atmosphere.”

At least one bank is taking advantage of the shakeout in the industry. Barclays Plc is emerging as a potential buyer of margin loans, according to people familiar with the matter. Tim Throsby, head of investment banking at the London-based firm, wants to pursue more corporate equity-derivative trades as part of a strategy to take more risks and make more money, he told investors in September.

Spokesmen for the banks declined to comment.

Geely’s Collar

Collar trades have also attracted scrutiny. The derivatives allowed Geely, for example, to quickly become the biggest shareholder in Daimler with a 9.7 percent stake. BaFin, the German markets watchdog, is probing whether the deal breached any local rules that require shareholders to disclose holdings exceeding a certain threshold.

Such trades, which let clients finance a bigger portion of the underlying stock, have been particularly popular in the past two years among Asian clients, according to one banker. They involve using offsetting put and call options to limit losses while forgoing some gains, but banks can still lose money if the shares plunge too quickly for them to protect themselves, said Stowell, the finance professor.

“It can happen theoretically and it can happen in actuality,” said Stowell. “Then they will lose a lot of money. That’s the big worry.”

Making ‘Friends’

Despite those caveats, the business remains attractive because it helps build relationships with the biggest and wealthiest clients, according to David Knutson, head of credit research for the Americas at Schroder Investment Management, which oversees more than $500 billion.

“You bring debt to the party, capital to the party, you tend to make a lot of friends,” Knutson said. “When you find an opportunity to develop a relationship, it’s very attractive.”

Some of those opportunities arose in late December. As CEOs across Wall Street fended off queries about the Steinhoff losses from their boards and prepared to tell investors, groups of bankers were already working on the next round of multibillion-dollar deals.

On Dec. 27, JPMorgan led a transaction that increased the size of a margin loan to HNA to $3.5 billion, filings show. The Chinese company had used the debt earlier in the year to purchase stakes in Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. and two spinoff companies from Blackstone LP for about $6.5 billion as part of a global spending spree it has since reversed.

The same day, Nomura and Barclays signed off on another trade with Geely. Using a derivative transaction known as a contingent forward, the banks bought shares in Swedish truckmaker Volvo AB worth about 3.3 billion euros and will sell them to the company when it gets approval from Chinese regulators, according to a statement and a person familiar with the deal.

“Complexity can be dangerous if it inhibits a genuine understanding, and an accurate calculation, of risks and exposure,” said Colombo, the former Morgan Stanley counsel. “On the other hand, a complex arrangement may present a very lucrative opportunity that ought not to be passed up.”

— With assistance by Cathy Chan, and Laura J Keller

Read again An Opaque $3.5 Billion Business Gives Wall Street a Hangover : https://ift.tt/2GwF3drBagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "An Opaque $3.5 Billion Business Gives Wall Street a Hangover"

Post a Comment